The pre-AC age: how did buildings in the Middle East keep cool?

Welcome back to LouBugWrites Edition 3! This week, I have evolved into an architecture acolyte for the first edition of the Oman series.

A quick preface and apology: This article is shorter than what I normally write as it was born only after I spent most of the previous week becoming one with my favourite armchair while battling a chest infection; I was therefore on a bit of a time crunch to get this published on schedule (thank God for coffee). Sleep deprivation and low lung capacity notwithstanding, I will be publishing every other week as normal moving forward, so subscribe for free to get notified about the next articles in the Oman series!

As mentioned in my previous article, I’ve been living in Muscat, Oman for a little over a month. As someone who poured over YouTube videos of unique housing design as a child (yes I was a weird kid, no I have not changed), the intricate detail and unique design of Middle Eastern architecture has emerged as one of my favourite features of this unfamiliar desert landscape. Unsurprisingly, traditional building design here is also holistic, taking into account temperature and solar intensity in every part of the building, which minimises reliance on air conditioning. This is something that is missed in many countries - such as the US - that have access to relatively cheap energy and therefore in-built design to combat the heat is a mere afterthought. These fascinating design features that battle the desert heat will be what we are exploring today…

First up, one of the most obvious features of Omani (and a lot of traditional Middle Eastern) homes: their colour. As anyone who has wandered around in bare feet in the summer will know, walking on pale-coloured flagstones is far more comfortable than scalding black tarmac. This is because infrared radiation (part of the spectrum of different wavelengths of light, of which visible light is also a part) is better absorbed by dull, black objects than white, shiny ones, and infrared radiation is experienced as heat. Reflecting as much of that heat away from a building as possible is essential when summer temperatures in Oman can skyrocket to 50°C or more (that’s 122°F for the Americans). This is perhaps one of the easiest ways to reduce heat in many different contexts worldwide.

A common external feature that most people imagine when they think of Middle Eastern architecture is the dome, and in Oman almost every mosque I have seen sports one on its roof. This includes the enormous Grand Mosque of Sultan Qaboos, whose dome sports a 9-ton chandelier from its centre. Domed roofs help with heat dispersion by allowing only small areas of the roof to be exposed to sunlight at any one time.

The Sultan Qaboos Grand Mosque, a fantastic example of a pale-coloured heat-reflective building that also features a dome. Credit: I took this photo

The go-to in Oman is to build with limestone, coral stone or Indian sandstone (in the case of the Sultan Qaboos Grand Mosque pictured above); pale-coloured rock that is more reflective, but white paint is also an option. Using stone or natural mud bricks also has other benefits besides reflectivity. Natural materials tend to absorb moisture during the night and release it by evaporation during the day, taking latent heat with it and producing a slight cooling effect. Production of these bricks also create far fewer carbon emissions than production of steel or concrete, but the former can be difficult or unpopular to use due to a high initial investment and lack of skilled workers. Using stone also creates buildings with thick, sturdy walls which have a higher thermal mass than thinner walls which helps to even out temperature fluctuations.

Nizwa Fort, another older example of traditional building design featuring the sandy-coloured thick walls and small window slots that maximise cooling. Credit: I took this photo

A fascinating external feature is a barajeel, or wind tower. This traditional structure creates a natural ventilation system by allowing hot air to flow down into the lower floors of the building, or underground, where it cools, circulates and then travels back up the tower once it has become warmed again. This can lower building temperatures by up to 10°C (50°F), which could remove the need for air conditioning altogether! Qanats - underground water channels - can also be used to cool the drawn-in air rather than simply relying on the lower floors. In ‘ The Sustainable City’, Dubai, barajeels are used to cool entire plazas!

A barajeel in Bastakiya, Historic Dubai Neighbourhood. Credit: one-thirteen on Flickr

Layout of buildings is also an important consideration when it comes to heat-proofing. Narrow streets between north-oriented buildings create sikkas - shaded walkways or courtyards that provide further cooling and also pedestrianise the local area. Having narrow entrances and exits to buildings has a similar effect, minimising solar gains and maximising shading.

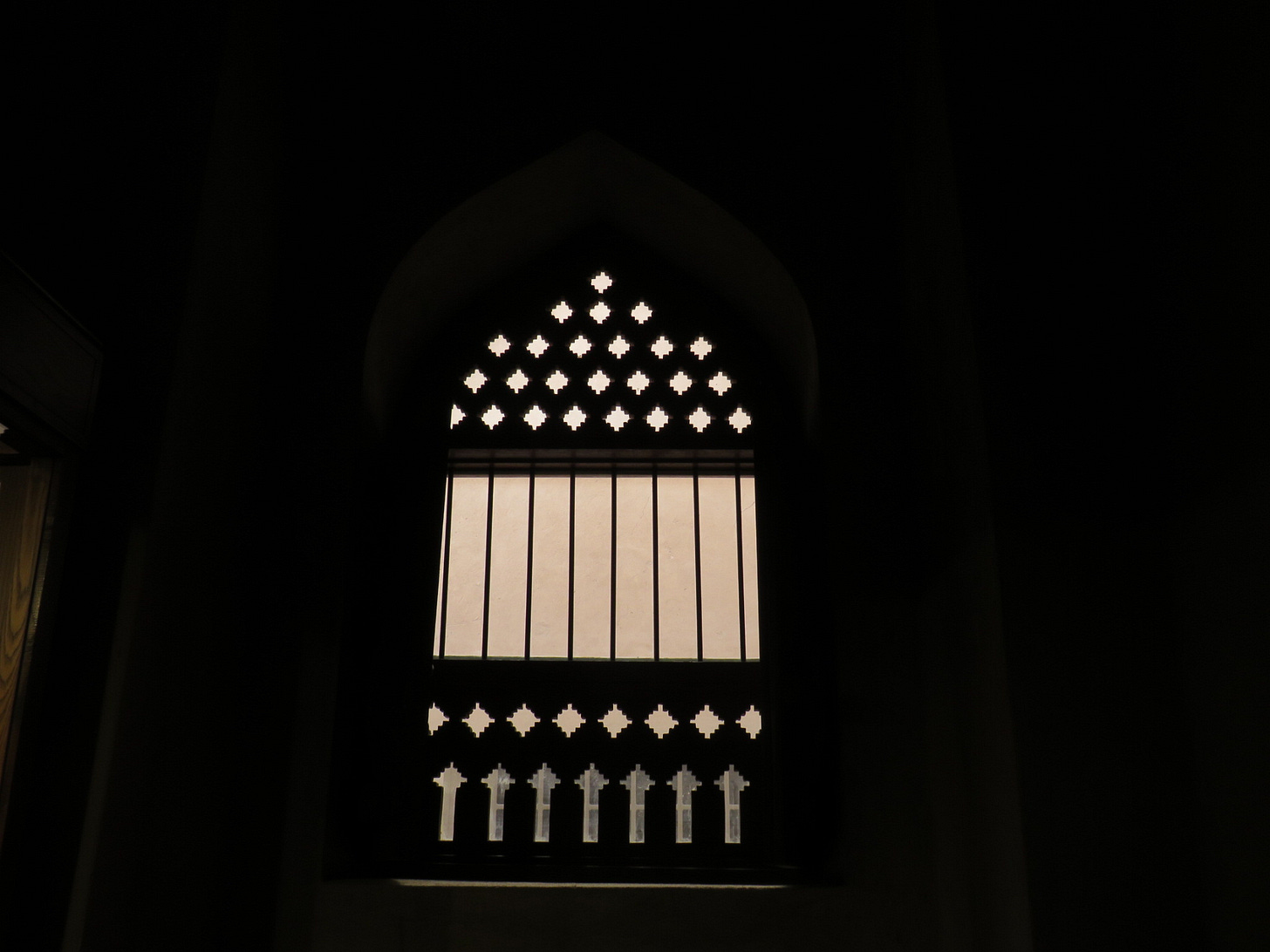

Finally, let’s take a look at traditional Middle Eastern window design. As with all features mentioned in this article, I am of course massively generalising these design features to cover a large continental area, but each country and even region will have its own unique design. But, generally speaking, windows are kept small and are often covered with mashrabiya, wooden latticework that allows light to enter but also creates a large amount of shading, again reducing those all-important solar gains and reducing the need for AC.

A wooden mashrabiya covering over a window opening at Nizwa Fort. Credit: I took this photo

It’s no secret that this is an important topic that will only become more relevant as the Anthropocene age advances and the world boils. Even at the current 1.1°C of warming produced by our post-Industrial emissions, 88% of US households use some kind of air conditioning equipment, and globally air conditioning use contributes to almost 4% of carbon emissions. With more countries - including my native Britain - destined to become increasingly AC-dependent, building a world based on traditional design features to maximise natural cooling has never been more essential.

What does the traditional architecture look like where you live? How does this help buildings to adapt to extremes of temperature? Got more recommendations for the Oman series? Let me know by leaving a comment!

If you’d like to learn more about more modern architecture that also minimises the need for AC, look into the Siemens’ Middle Eastern HQ in Masdar City, Abu Dhabi. It is one of the first buildings in the region to be awarded with an LEED platinum certification from the US Green Buildings council, cementing it as one of the most sustainable buildings in the world. (see the links below for more information)

Sources for this article

Beat the heat: Sustainable ways to make buildings in the Middle East cooler

The US Can Borrow From the Middle East to Cool its Cities - TIME

Energy efficient buildings in warm climates of the Middle East

Exploring the Beauty and Elegance of Traditional Omani Architecture

U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)

Hi Thomas thank you so much for leaving this comment it’s made my day! Congratulations on being the first person ever to comment on any of my articles and I’m so glad you’re enjoying it!

Oh my gosh Louisa I'm only about 60 seconds into reading this post and I'm already FASCINATED. I think I might've missed my calling to be an architect or something. I really love learning about this stuff. I'm subscribing. I like a lot of your other articles talking about some of the other burning questions I have. Now...let me get back to your article.